A Detailed Guide to Biological Considerations for Mini Implants in Orthodontics

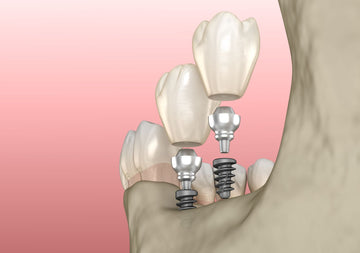

Mini implants, also known as temporary anchorage devices (TADs), have revolutionized orthodontic treatments by providing a reliable anchorage solution. Unlike traditional dental implants, mini implants do not rely on osseointegration for stability. Instead, they depend on primary mechanical stability and, over time, secondary stability supported by bone remodeling. Understanding these biological principles and optimizing placement techniques is crucial to maximizing their success. This extended guide delves deeper into the biological factors that influence the success of mini implants and offers practical tips for clinicians, covering aspects such as bone quality, implant placement, stability, and patient-specific factors.

Primary Stability: The Foundation for Mini Implant Success

Primary stability is the initial mechanical retention achieved immediately after the mini implant is inserted. This stability is vital because it determines the implant's capacity to withstand orthodontic forces immediately or shortly after placement.

Factors Influencing Primary Stability

Bone Quality and Quantity

-

Cortical Bone Thickness: Mini implants derive most of their primary stability from cortical bone. A thicker cortical layer provides better resistance against displacement.

-

Bone Density: The density of the cancellous (trabecular) bone surrounding the implant threads also contributes to primary stability, albeit to a lesser extent.

Close Bone-Implant Interface

A tight fit between the implant threads and the surrounding bone ensures mechanical retention. Any excessive gaps between the implant and bone reduce stability and increase the likelihood of failure.

Implant Design Considerations

-

Thread Pitch and Depth:

-

Coarser threads are advantageous in softer bone as they increase retention by engaging more bone volume.

-

Finer threads are better suited for dense cortical bone, where a compact design minimizes insertion torque.

-

Implant Diameter and Length:

-

Choosing an implant diameter and length that aligns with bone thickness and density optimizes stability.

-

Implants that are too short or narrow are prone to loosening under orthodontic forces.

Insertion Techniques

-

Torque Control: Excessive torque during insertion can damage bone and lead to microfractures. In dense bone, pre-drilling reduces torque while preserving bone integrity.

-

Insertion Angle: The implant should be placed perpendicular to the bone surface or along its long axis. Angled insertions can lead to uneven stress distribution, reducing stability.

Secondary Stability: The Role of Bone Remodeling

While primary stability is mechanical, secondary stability develops biologically over time as bone remodels around the implant. Secondary stability becomes significant in long-term treatments where bone healing processes influence implant retention.

Bone Healing and Osseous Adaptation

Osseointegration vs. Fibrous Encapsulation

-

Osseointegration: Although mini implants are not designed for complete osseointegration, partial integration occurs as new bone fills gaps at the implant-bone interface.

-

Fibrous Encapsulation: If the implant is unstable during healing, a fibrous tissue layer may form instead of bone, leading to loosening.

Factors Enhancing Secondary Stability

-

Bone Healing Potential: The patient’s age, systemic health, and local vascularization influence the speed and quality of bone healing.

-

Loading Protocols:

-

Immediate loading with light forces promotes favorable bone remodeling.

-

Excessive forces can disrupt healing, leading to implant failure.

-

Surface Characteristics: Mini implants with rough or coated surfaces may encourage better bone apposition compared to smooth implants.

Bone Quality: Key to Successful Implant Placement

Bone quality varies significantly across anatomical locations and between individuals. Understanding these variations helps in selecting the right implant design and placement technique.

Bone Density Classification

Orthodontists often classify bone density based on Misch's classification:

-

D1 (Very Dense Bone):

-

Found in the anterior mandible.

-

Offers excellent primary stability but is poorly vascularized, potentially delaying secondary stability.

-

Pre-drilling is often required to reduce insertion torque.

-

D2 (Dense Bone):

-

Found in the posterior mandible and anterior maxilla.

-

Ideal for mini implants due to its balance between strength and vascularization.

-

D3 (Moderate Bone):

-

Found in the posterior maxilla.

-

Requires coarser threads for improved retention.

-

D4 (Poor Bone Quality):

-

Found in the retromolar and posterior maxillary regions.

-

Often necessitates alternative anchorage strategies or specialized implant designs.

Clinical Tips to Avoid Common Pitfalls

-

Over-Tightening the Implant:

-

Excessive torque during placement can cause microcracks or necrosis due to overheating. Use controlled, gradual insertion techniques.

-

Avoiding Micro-Movements:

-

Any wobbling during placement creates instability. The implant should engage the bone in a single, smooth motion.

-

Monitoring Cortical Bone Engagement:

-

If the cortical layer is insufficient, additional precautions (e.g., longer implants or alternative anchorage) may be necessary.

Patient-Specific Factors

Systemic Health Conditions

-

Osteoporosis: Reduced bone density decreases the likelihood of achieving primary stability.

-

Smoking: Impairs bone healing and increases the risk of peri-implantitis.

-

Diabetes: Delayed healing and increased risk of infection necessitate rigorous monitoring.

Age and Gender

-

Age: Older patients often present with reduced bone density and cortical thickness, necessitating careful planning.

-

Gender: Hormonal differences, especially in postmenopausal women, may influence bone remodeling and healing.

Post-Operative Care and Maintenance

Mini implants require meticulous post-operative care to prevent complications and ensure stability.

Hygiene

-

Educate patients about maintaining cleanliness around the implant to prevent peri-implantitis.

-

Use chlorhexidine rinses as part of routine care.

Force Application

-

Apply light forces initially to allow healing and bone adaptation.

-

Gradually increase forces as secondary stability develops.

Regular Monitoring

-

Conduct follow-ups to check for signs of inflammation, infection, or loosening.

-

Use radiographic imaging to assess bone remodeling around the implant.

Seven Additional Resources for Further Study

-

Melsen, B. (2005). Mini-Implants in Orthodontics: Innovative Anchorage Concepts. Quintessence Publishing.

-

A comprehensive guide on mini implant concepts, including design, placement, and clinical applications.

-

Baumgaertel, S., & Razavi, M. R. (2016). "Temporary Anchorage Devices in Orthodontics." American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics.

-

A detailed overview of TADs, their uses, and placement strategies.

-

Park, H. S., et al. (2001). "Clinical Applications of Mini-Screw Implants in Orthodontics." The Angle Orthodontist.

-

Explores the versatility of mini implants in various orthodontic scenarios.

-

Papadopoulos, M. A. (2008). Orthodontic Treatment with Miniscrew Implants. Wiley-Blackwell.

-

Focuses on clinical techniques and case studies for mini screw usage.

-

Ludwig, B., et al. (2008). Mini-Implants in Orthodontics: Principles and Practice. Springer.

-

Covers principles, biomechanical considerations, and clinical applications.

-

Deguchi, T., et al. (2003). "The Use of Miniscrew Implants in Japanese Orthodontic Practices." Journal of Clinical Orthodontics.

-

A regional perspective on mini implant applications and challenges.

-

Graber, T. M., Vanarsdall, R. L., & Vig, K. W. L. (2016). Orthodontics: Current Principles and Techniques. Elsevier.

-

Offers broader insights into anchorage solutions, including mini implants.

0745 100 497

0745 100 497